I østerled. Arbeidsdag 2.

Almaty 07.01.2021

Av Knut Erik Aagard.

(…who has insisted on publishing this interview in English.)

Pål Steigan (the Editor) and the interpreter/photographer (me) are in Kazakhstan to try to make sense of this far-away country in the middle of Asia, about as far from any ocean as you can get. Kazakhstan is the biggest, but not the most populous, of the five Central Asian republics that more or less willingly left the Soviet Union as it decided to implode in 1991. We are not here as election observers – the only voter we ever saw vote, was actually the president of Kazakhstan voting for himself twenty-five feet from my mobile phone camera. We are here as independent analysts paid for by the Republic to make our own objective analyses of the country at this crossroads in time. So are we objective? Who is objective? Nobody is objective, not even (or especially not) science. But we try to be honest. We stay at the best hotels, we have an official servant at each finger, they get us all we need or ask for, drive us wherever we want to go, so to question our objectivity is just being objective. In order to counter such misgivings, we have interviewed not only a host of officials, but also three dissidents, two that we dug up ourselves, and one who was helpfully supplied for us by the government.

Today we are interviewing one of our own dissidents, in Almaty, the former capital, just down from Medeo, where the photographer had the dubious pleasure of trying a 1959 pair of Russian speed skates, which may have been, but probably were not, Boris Zhilkov’s. Dubious pleasure, as the photographer hasn’t stood on a pair of skates since (approximately) 1959, and found his ankles are more shaky now than they used to be.

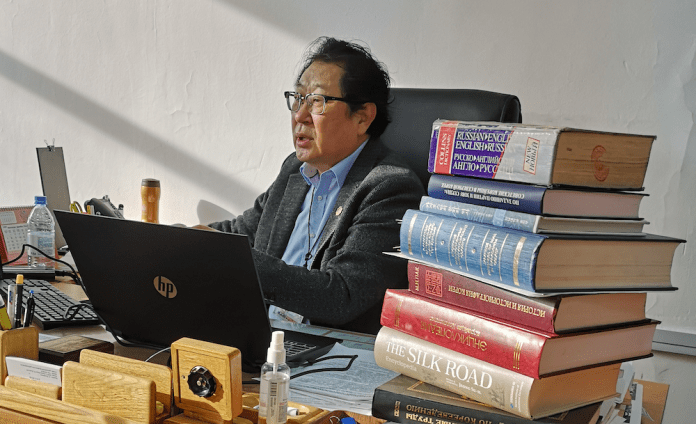

Our chosen dissident today is Professor Dr. German Nicolayevich Kim, director of The International Center for Korean Studies at the Al-Farabi Kazakh National University in Almaty. He works in a classical Soviet style university from the sixties or seventies, strictly functionalist but not very functional, nor beautiful. These universities look exactly the same in Vladivostok, Kaliningrad or in Tashkent, to mention just three USSR cities very far away from each other. In short, they look very dull.

Professor German Kim is originally a germanist and speaks fluent and elegant German. But as some know, anybody born Herman will in Russia automatically be called German. So to evade misunderstanding we have restored his European name Herman for the occasion. Herman speaks a lot of languages, European and Asian, as will become clear. We had decided to conduct this interview in Russian with me as interpreter, as I speak Russian tolerably well. One possibility was German, a language Pål knows well and I do not. And it seems Herman doubted my proficiency in Russian as much as I distrusted his pronunciation of English (both rightly), but the editor (Pål) decided for that language. That is why this interview appears in English in a Norwegian newspaper. We apologize, but it was simply too laborious to transcribe the interview twice. Happily, both Herman’s and my English show up substantially better on the printed page than they actually sounded.

This interview was enlightening to Pål and to the photographer (alas, not interpreter today). We learnt very much more about a rather small part of a rather typical Post Soviet Central Asian republic, and we learnt a little more about the large world surrounding it. The discussion centered on two topics, Kazakhstan and Korea, so possibly the interview will have been clipped in two by the time you read it. As the photographer was late getting his gear going (the gear and all our luggage were left in Frankfurt am Main under mystical circumstances), we jump straight into Herman’s introduction of himself:

Herman Kim: .. the last seven years I spent in Korea, teaching at several universities in that country. Now I am adapting myself, again, to my own country, to my home country. I have been here only on holidays, sometimes here in Almaty, but mostly traveling all over the world. I wanted to get to know South East Asia, for instance Vietnam, two times to Cambodia, also other countries, since before, you know, I never had the chance.

My main academic interest from early days when I started to study for my first PhD dissertation, was the Korean community, the Korean diaspora in Kazakhstan. But at that time, the Soviet period, before the Gorbachev time, it was prohibited to study the history of the deported people, the «unreliable people». So my first dissertation was about the history of Soviet Koreans in Kazakhstan. And then, I got an invitation from the South Korean government – at that time my Korean language was like zero – for they several times presented my papers at international conferences. And the authorities of South Korea decided they wanted to help me. You know, at this time, the end of the eighties, the early nineties, it was impossible in this country, the old Soviet republic – before the collapse of the Soviet Union – it was a very hard time – there was no chance to make studies.

So they invited me and I spent 6 months learning the Korean language at the Seoul National University. And then, after one year, they invited me again, as a researcher, a visiting scholar. At that time my teacher, professor Yi Kwanggyu (1932-2013), a very famous Korean scholar, received one of the first Korean PhD’s in the German language field, in Austria, at the Vienna University. He spoke several languages. At the time my Korean was very poor, so I spoke only German. But he insisted that I study not only the Koreans in the Post-Soviet space, but worldwide. He said: You know several languages, so for you tit will be easy. For I also studied Latin for four years, I know Spanish, French, Russian, and a little Italian, but no Ancient Greek. You know, in the Soviet time, in the early seventies, in Europe and also in The Soviet Union, for classical world history studies, all students were still required to know Ancient Greek or Latin – so I was studying Latin. That was a good basis for easily learning the European languages. The Korean language was not a heritage language for me, my parents did not speak Korean to me, no school, no education, no nothing.

Photographer: But your family roots are Korean?

HK: Yes .. I am a Korean overseas, although there is no sea between Korea and The Soviet Union, where I was born, in Almaty, Kazakhstan. I am a fourth generation Korean abroad. That is, my great grand-parents moved in the early wave of Koran migration to the Russian Far East. My grandparents were born there, in the Far East, and also my parents were born there. They lived about eighty years, and being suspicious were deported during the war. I was born here in Kazakhstan, the first generation of Koreans here in Kazakhstan.

Photographer: So you have been studying, so to speak, your own people, as a first generation Korean migrant due to deportation during the communist era ..

HK: Yes. That’s why I wanted to study the history of my people, I mean the Korean diaspora, in Kazakhstan, but also in The Soviet Union, starting from the very early history, that is, the Korean migration to the pre-revolutionary Russian Empire. So that is why I wrote a lot – a lot – of books:

35 books and over 200 papers. Mostly they are about Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Koreans. This is the first field of my activities.

Secondly, you know, I published this book: The History of Korean Immigration (gets up, gets the book) in three volumes, that covers the period from the late nineteenth century up to the year 2000. This book has been translated into Korean and published in Korea.

Photographer: But not into English?

HK: Just now it is being translated, it is in the the process of being published, at the Berkeley University. That is my second great academic interest.

And the third – because I am very much involved in diaspora life here in Kazakhstan – I have served 24 years as vice-president of The Korean Association in Kazakhstan. And this ethnic association .. is very strong. Very strong compared to many other ethnic organizations. There are in Kazakhstan over 40 ethnic associations, and our association is the strongest, well established, with a lot of activities. For: Also we have two Koreas. It is something very unique, that the diaspora has two kin-states, two fatherlands, North Korea and South Korea. So we (the association) are in between. And these two Koreas (in Kazakhstan), they are in conflict. We are in the middle and we have a mission. A very special mission: To be the mediator between two Koreas, since for us Korea is two motherlands. We have initiated a number of projects, many within the conceptualization of public policy as a soft power. We did what the politicians could not do.

For example, we organized several contests of Taekwondo, two versions of Taekwondo, North Korean Taekwondo and South Korean Taekwondo. We invited competitors from both countries. We invited .. and we paid. We have invited singers and dancers, like the Pyongyang ensemble – 18 people. Fifteen actors and three from the North Korean KGB (laughs). But we paid for them, and the Grand Prix went to the North Korean female singer – ten thousand dollars. They were so happy!

This took place during the controversial period of Lee Myung-bak (president in South Korea 2008-2013, formerly director of Hyundai). The relations between the North and the South were then so sharpened, so bad .. so dangerous that many thought that a new Korean War will start tomorrow! I said No! Never! (laughs). We organized, here in Kazakhstan, in The Kazakh National University, two great Freedom Conferences. And also the North Koreans came. They never met in Seoul or Pyongyang, but they both came to Kazakhstan – to neutral territory.

And yes! We talked, we also spent some unofficial time together. Afterwards, we met – in China. The second time – in Dandung, a small town on the border, across the river. There we had conferences and talks, in China, nearer to the homeland. Russian Koreans have organized stockcar races, inviting northern and southern Koreans, there were teams from other Central Asian republics also participating – I still have a T-shirt with my name on it from one of these races, running all through Central Asia, three times crossing the Kazakh border. Actually I wanted to join the race for some of the distance ..

Pål: Excuse me, Herman. At this point I would like to interrupt you for a moment. You see, since my visit to Korea I have followed the situation there, and among other things I made a very nice interview with a South Korean bishop, a protestant bishop, who was arrested because he called for Korean unification. He was in prison for fourteen years or so, and he never gave up this idea of unification. Now, in the Trump era, with his overtures to the North Korean leader, I also followed the talks between the two countries. And the Vladivostok meetings between Vladimir Putin and the South Korean Premier. They have a grand strategy of infrastructure, trade etcetera – I don’t need to tell you about all that .. (a reunited Korea will have an explosive economic potential combining Japan, China, Russia and South-East Asia in one transport and trade sphere) .. but I am quite exited about the perspectives that open up, because a unified Korea will be one of the biggest economic powers in the world, as you well know.

HK: Yes. You know, for six years I have been writing essays for our diaspora newspaper, essays about unification, prospects and problems. I write in Russian, but the editor has my essays translated into Korean, in some editions one page for each language, dual lingual editions of the newspaper. Can you see what is written here? (showing the photographer the frontispiece of a book written by HK).

Photographer: «Объединение Кореи неизбежно». Which (of course) means «Korean unification is inevitable».

HK: I have written around two hundred essays concerning various topics connected with unification. For our people don’t know anything about North Korea, they mostly read Russian language bullshit. These peopla are not journalists, they are small people who explode small bombs every day to earn a lousy living by bombs. In the course of three whole months they were writing that the South and the North are actually at war. (The photographer, who follows Russian media, cannot corroborate this information. Maybe Kim here is referring to Russian-speaking South Korean sensational journalists in Kazakhstan?). But I explained that there is no war, there will not be a war. And this I do to enlighten our Kazakh public. No war. War is over.

When I plan an essay, I read a lot, in many languages and I try to find the golden middle. And I never directly criticize the North Korean leader. Never. That’s why North Koreans also like it and publish my essays, even on the first pages of the party newspaper. But I write these essays for our half million Korean diaspora in Kazakhstan, to enlighten them. I tell them: Germany is reunited, Vietnam is reunited, China is reunited. Jemen is reunited. Why not Korea? A young person will say – I don’t know, it’s none of my business, I don’t care, it doesn’t interest me – And that is, you know – a shame. A shame of the diaspora, a shame of the people.

Photographer: We perfectly understand, and I understand that it must be difficult to keep up the memory of unity and belonging during four generations abroad. And that it is important to foster and strengthen these ideas of unity, even here in Almaty. It is important to the Korean minority and also interesting to politically minded people in the West, like Pål and me, since the «Korea Question» is of capital geopolitical significance. With my poor knowledge of the history of Korea before the war, and of the war after the war – I actually remember the day it ended in 1953 – I am beginning to wonder: Why did the Koreans start to migrate in the first place? Did it start with the Japanese colonization in the middle of the nineteenth century? Is that correct?

HK: That is one of the reasons. But initially the Koreans began to leave their country from the northernmost provinces, from Hamgyŏng-pukto, at that time very close to no man’s land – no Chinese, no Russians. Then there was a treaty made, and this territory was assigned to Russia. And you know – South Korea is for agriculture. But North Korea is full of mountains and minerals and water, and there are few chances for field agriculture, for rice, grain and so on. All the food was in the South. So when there was a bad harvest in the North, or bad weather or cataclysms, then many people died from hunger. Why? Because at that time there were no communications, no railways, no ships on the rivers, nothing. Transportation of food, grain, rice from the South to the North took two to three months – and so people died or migrated.

And you know, when I started studying overseas Koreans or Koreans abroad, or Korean emigration, I also studied Japan. I have been to Japan a dozen times. And there I was told that during the colonial rule, twelve years after the annexation of Korea by Japan, the number of mortal cases from hunger was decreasing. I heard this several times. Why? The reason was first, vaccination, second, transportation of food. And so, average life expectancy was growing during colonial rule! For 12 years!

When I wrote about this my South Korean professors – didn’t like it. But they had to admit that it was true. I told them to read properly what I had written. The Japanese didn’t do it because they liked the Korean people. They did it because they needed the manpower in the North, where also the minerals are located. It was a virtue by necessity. They built roads, bridges and so on. Why? Because they were preparing for a war against China.

Photographer: I perceive that before The Great War Korea was a Japanese colony. When Japan lost the war, Korea was liberated from two sides, from the North and from the South. And what ought to have become one unitary post-colonial state actually became two administrative entities divided along the 38th meridian, where the Chinese and the American forces met each other. After the armistice, free elections were promised for a free and united Korea, but the promise was never heeded (just as similar promises were never kept in Vietnam in 1954-56, sparking that American war). Consequently, the free Koreans from the North in 1950 attacked the Americans south of the border, in order to regain the other half of the country – a fair demand if you ask me – initiating the so-called «Korean War». In the first phase of the war the Koreans met with success, and drove the southern generals and their American patrons down to a small territory at the tip of the peninsula. So the Americans launched a great offensive, totally superior in troops and weaponry. The US even had UN backing. It so happened that the Soviets for some obscure reason this year boycotted the Security Council and were prevented from vetoing the decision to accept the American aggression as being within the framework of International law. In face of the massive US offensive China intervened, with some Soviet assistance, in favor of the Koreans.

The result was militarily a stalemate, a statu quo ante along the 38th meridian, socially a catastrophe, economically a ruin, and politically a divided Korean people pawned to two new colonizers, the communists and the imperialists. The Chinese soon went home, leaving behind a strong patriotic communist regime. The Americans did not go home – they are still there – but established the brutal puppet dictatorship of Syngman Rhee (the exiled Korean president between 1919 and 1925), in 1961 replaced by the no less brutal General Park (Park Chung Hee) as a dictator after a military uprising, until he was murdered in 1979. Needless to say, these two dictators pursued policies aimed at furthering American interests in the West Pacific, a hegemony felt ever since, not least at the present time.

(At this point in the interview Pål cuts the photographer short, apparently sensing some muddled thinking from his side, and embarks upon a lecture about the Chinese, who doubtlessly did much good for Korea, and about Kim Il Sung, who was not at all as bad as he usually is portrayed in the West. Pål also reminds us that Chinese troops in Korea were volunteers, that the northern leader Kim Il Sung had his bases in China, and also that the Americans a few years ago had dropped two atomic bombs over Japan and were planning to use this weapon again, in the Korean war. Point taken and granted, the photographer resumes the thread he was in the process of spinning).

Photographer: Now, to resume my preparation for the question to you, Professor Kim, I would make the point that any Norwegian politician, or newspaper editor, or man-in-the-street, would tell you today that the Korean War was fought between the North Koreans and the South Koreans. I see it differently. It seems to me that the so-called Korean War was fought by the Korean people against American aggression. Am I on the right track? A side question: A friend of mine and a colleague of yours, professor Vladimir Tikhonov at the University of Oslo, told me he is inclined to believe that the present Korean urge for reunification is stronger in the North than in the South. Your comment?

HK: Let me start with Knut Erik’s (the photographer’s) remarks before I respond to those of Pål. I agree that the Korean War .. or The Unknown War .. took place on Korean soil, but this war was fought between capitalism (or imperialism) and communism. Of course, Syngman Rhee, the leader of South Korea, and Kim Il-Sung, they both wanted to control the whole Korean peninsula. That is true. Both of them. It is true that both prepared for the war. That’s also true. But I am sure that this war would never have happened if Stalin and Mao Tse-Tung had said to Kim Il-Sung: No! Don’t touch South Korea!

You know, Mao Zsedong and Kim Il-Sung visited Stalin two times, asking him: Please, permit us to attack South Korea. We are sure that we shall overcome the South. We shall win! The first time, Stalin asked: Are you sure that you shall win? But Mao Zsedong was not completely sure, so Stalin said: Go! Come back when you are prepared! Then, the second time they came, Stalin said: OK. You may attack. But The Soviet Union will not take part in the war. We shall assist you with infrastructure and arms. That’s why the Chinese volunteers, under Peng Dehuai (general and defense minister of China), they should keep their word. They were the ones involved in the war.

And you know, this was during the long epoch of The Cold War. I guess that South Korea was the focus or epicenter of The Cold War. For several reasons. And the Kim Il Sung regime was unique. Not like Erich Honecker’s regime. Honecker was a good guy compared to Kim Il Sung. The relations between East and West Germany – they were OK. People could visit each other .. the West Germans visited the East Germany very easily (until the wall was built in 1961?) .. The exchange of the Eastern Mark and the Western Mark was 1:2, but in the black market it was 1:20! Many West Germans came to East Germany to eat real well .. The difference between East German and West German GDP (Gross Domestic Product) was very small, the one only four times bigger than the other, small compared to the differences between North and South Korea. (Pål and the photographer both think professor Kim tries to express the idea here, that German reunification was much easier than Korean reunification is likely to be).

This means: I never talk of the reunification of Korea in ten, fifteen or even 25 years. It is not possible, because reunification through war is not the model. No country outside can influence or impact to reunify this country. It is not comparable to Germany and Gorbachev. It will take quite a long time for North Korea to develop and change. But in the end the difference (of the economies) will be small .. and only then will the relation be normalized, so that people can travel and visit each other. But for that to happen, the gap between the economies must be reduced. I think, like you, Pål, that a united Korea will be a very strong country. I agree. But it will take .. maybe a hundred years.

But what is a hundred years? A hundred years in the history of Korea is nothing. Korea has been one country for 3000 years (laughs). A hundred years is nothing. This is what I mean when I write that reunification is inevitable.

But this idea of Kim Il Sung of a confederative reunified Korea at once .. First, the South Koreans said no, no, no, find a better idea! But now they say: It’s a good idea! Let’s think about it! Like: «Two states, one country», with normalized relations. When North Korea becomes an economic success, becomes like, or similar to South Korea .. it can happen. The Chinese leaders insisted that Kim, the young leader, follow the Chinese model, but he did not want that. He was afraid of losing control. «First economy and then ideology» (laughs). But now .. in his last speech .. when all directives and all 5-year plans have collapsed .. now I note: He is going to change.

The word that the North Koreans most dislike is the word reform. I used the word once, several years ago in North Korea. They said no, no, no! We don’t use that word. Changes, changes, not reform (laughs). When they hear the word reform they think of something bad. I suspect that in the near future, we will see big changes in North Korea.

Photographer: I find it funny that change and reform – two identical words – are very different.

HK: Yes! That’s funny! Change is a euphemism for reform or vice versa (laughs heartily). In the future, in the far future – reunification will be and should happen. In the far future, not in the near future.

Let us imagine that North Korea collapses. What will happen then? This will be a big headache for China, because of refugees, an influx of people flowing over the border. North Korea can collapse. The South Korean economy is not strong enough to absorb the North Koreans. The West German economy was much stronger, and better able to absorb the East German population. 62 million Germans in the west and 18 million Germans in GDR, in the east, and the territory of the west was only twice the size. The East Germans were well educated, qualified people, all had flats, housing and cars and so on. No luxury, but quite OK.

Pål: I have an idea that Korea might have a bearing on a country like Kazakhstan. First, of course, because there are many Koreans here, but also because of the ingenuity and creativity of the Korean people as I have seen them in South Korea. They really created – like the Germans did, and even in a better way, an industrial miracle .. formally as a capitalist system but in reality under a sort of planned capitalism, with chaebol (conglomerate) playing a very crucial role in a state plan (HK: Yeah). So we see some similarities to the situation that Kazakhstan is facing. Your immediate roots are in the communist past, you do have a sort of capitalism, but you haven’t yet solved this seeming contradiction between plan and market. It might be that Koreans are better positioned to solve this riddle for Kazakhstan than the Chinese are. For they have a different experience. What do you think?

HK: Yeah. You are looking in the right direction! South Korea still has very good prospects for a strategic relation and partnership with Kazakhstan. Formally, the agreement of this strategic partnership was signed in 2009. But this partnership exists only on paper! For there are no activities to underpin this strategic partnership. I was working for the Kazakh Institute for Strategic Studies under the president of Kazakhstan when I came home from abroad in 2006. I received an invitation from the Think Tank of Kazakhstan to cover the relations of Kazakhstan with north east countries, mostly with Korea. The Think Tank has been working for four years and has produced many reports (gets up, gets a book by HK). This book is for the government, for the ruling party, for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I wrote monthly, every month. And this is my book in two volumes ..

Photographer: A good book cannot be too long. A bad book cannot be too short ..

HK: (laughs) The first volume is a monograph. The second volume is a collection of my reports.

.. Since the early nineties they invested a 100 million dollars. For the newly established republic this was big money, a hundred million dollars. But this investment came from South Korea. And then, there was this financial crisis in Asia. Many South Korean companies left Kazakhstan, in the nineties, in 1997-1998. But then they came back, I mean the small and middle sized companies. And new people came. Although, strictly speaking, only a few actually came back, mostly they were new people.

But since then, from the middle of the first decade after 2000, Kazakhstan receives a flow of Chinese investments. South Korea has lost its position in big business. Governmental business. State business. Oil. Precious, metals and so on.The biggest buyer in Kasakh economy is the state.

The South Koreans are now only to be found in small and medium-sized business. There are no big projects. This means that South Korea and Kazakhstan missed the chance to become strategic partners.

In my opinion, the focus of interest of the South Korean government and leadership switched from Kazakhstan to Uzbekistan. During the last visit of president Moon Jae-in to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in 2018, in Tashkent they concluded trade agreements and investments for eleven billion dollars. In Kazakhstan only for $900 million, not even one billion.

Why? Because President Mirziyoyev had continued the policies of the first president, Islam Karimov, that Korea is Partner Number One! And they have an agreement of a special, a very special cooperation. They have given South Korean companies so many preferences. The relation is so close!

If I travel to Tashkent, I see so many people, school children and old ladies .. they want to talk to me in Korean. They will greet me in Korean. And I say: Oh, sure! They want to make photos with me. And a crowd of people gather behind me, who want to be selfied with me! Maybe somebody told them that I look a little like this Korean movie-star. Maybe, I don’t know (laughs). And I say: I am not Korean, I am from Kazakhstan!

So I am afraid the chance was missed.

Photographer: So the Kazakhs slept in class and let the Uzbeks take the advantage!

HK: Yeah. There are several reasons for this. There is the immanent or local reason. Next, what has Uzbekistan actually been doing? The hospitality of the Uzbek people is so sophisticated that all South Koreans .. not only Koreans, but all foreigners who visit Uzbekistan, they all become fans of Uzbekistan. And the culture of Uzbekistan is so different from the one in Kazakhstan, and the food. If you look at Almaty, you will see that here in Almaty there are more Uzbek haut cuisine restaurants and cafés than Kazakh! The natural beauty of Uzbekistan, and the fruits and vegetables, from the Fergana valley, they were famous in the whole Soviet Union. In Kazakhstan we import a lot of food, fruit and vegetables, from Uzbekistan. Which means: If South Korea decides to invest a bulk of money in Central Asia, then, from now on, it will be in Uzbekistan.

But there are several reasons for the success of Uzbekistan. The population of Uzbekistan is bigger, it is the biggest in Central Asia. The Uzbeks learn the Korean language very quickly. It is much easíer to find a translator or interpreter from Korean in Tashkent, or in any Uzbek city or town, than here. Why? Because Uzbekistan and Korea long ago signed an agreement on migrant workers. Every year five thousand Uzbeks go to work in the plants and factories of South Korea for two or three years. In this period, they learn the Korean language very fast, very well! When they come back with revenues, or they send revenues to their relatives, they establish small businesses. They establish small businesses. Therefore, maybe one tenth of the Uzbek population is grateful to the Koreans, who gave them a chance to work, to establish businesses and learn the language.

Photographer: Was it Islam Karimov, the first president who died in 2010, who was so farsighted?

HK: Exactly, Knut Erik. And therefore, in Uzbekistan, the respect for the local Korean diaspora is very high among the Uzbeks. I would myself not like to give a characteristic of the Koreans, what is good in a Korean. But all, you know, not only Uzbek, but also other people, typically say that Koreans are reliable people, they are hard working people, they are clever and smart, they understand how to make money, they share the money: They make money and they share money! They are very successful, in all spheres they are successful, in politics, culture, economy and sports and so on.

Photographer: This is extremely interesting, Pål. Should we now try to direct the discussion a little toward Kazakhstan?

Pål: Yes. This was all very unexpected for me. I did not know this. Let’s talk about that in the next session.

oss 100 kroner!

oss 100 kroner!