The Ukrainian national anthem has a somewhat sombre title: ‘Ukraine Has Not Yet Died’.[1] Still, its third line promises that its enemies will disappear ‘like dew in the sun’, although that does not quite seem to be the case at present. Ukraine is teetering on a cliff-edge, unable to pay its bills. Behind the protests in Kiev (Kyiv) lie enormous economic problems – and a dark historical legacy.

(Translated by Guy Puzey)

The till is empty

Ukraine went through many difficult years following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Its gross national product fell dramatically, while industry stagnated. During the last decade, however, the country experienced a few years of strong growth before the financial crisis hit with full force. Today, Ukraine only has enough currency reserves to pay for less than two months’ imports, and a situation with anything under three months’ reserves is considered critical. Things are especially bad as the country has an international trade deficit. This derives primarily from the fact that Ukraine is totally dependent on gas imports from Russia.

For the same reasons, Ukraine has run up considerable debts that it cannot pay. This is the reason for the breakdown in negotiations with the EU, which in turn triggered the major protests in Kiev. The deal offered by the EU was simply not good enough. Indeed, it was far from good enough.

And what can the EU really offer Ukraine? The EU is deep into the sixth year of its own crisis. What the European Commission has to offer its own poor members are more cuts and a prospect of many years of stagnation and decline. And the EU is almost just as dependent on Russian gas as Ukraine is.

Brain drain and population decline

From 1994 to the present day, Ukraine’s population has fallen from 52.2 million to 45.5 million: a drop of 6.7 million in less than 20 years. Those who have left are often those with a good education and contacts, so this represents a dramatic brain drain. At the same time, the birth rate is extremely low and the death rate high. In 2009, it was estimated that 35% of the population lived below the poverty line.

On the other hand, Ukraine has strong industrial foundations inherited from the Soviet Union. In the eastern areas around the Don, there is a strong metal industry and strong heavy industries building aircraft, ships and military materiel. There is also an advanced electronics industry and a space industry. There are rich mineral deposits, with the country producing large quantities of both coal and steel. But there is little oil or gas.

The western parts of the country have some of the most fertile topsoil in the world. The Ukrainian black earth belt has deep, rich soil and high agricultural productivity. Ukraine is one of the world’s leading grain exporters.

West versus east

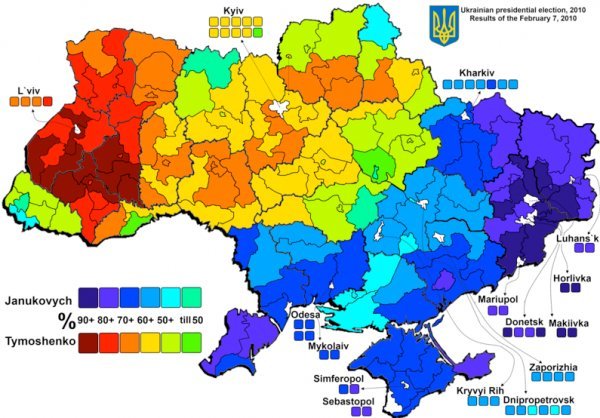

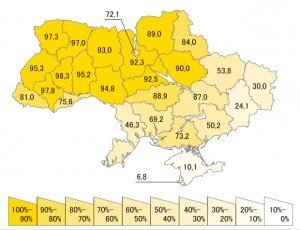

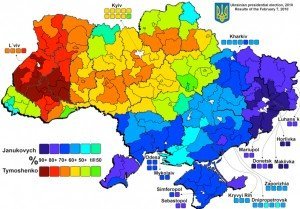

The majority of the population are Ukrainian, but there is a large Russian minority, especially in the east, where the industry is too. The pay is markedly higher in these industrial areas than in the country’s western regions. The Crimean peninsula is predominantly Russophone, and the Russians were furious when Nikita Khrushchev transferred the peninsula from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic to the Ukrainian SSR. Russia still has a naval base at Sevastopol under a lease agreed with Ukraine.

A linguistic map shows that the non-Ukrainian populations (mainly Russians) are greatest in the east.

Political division

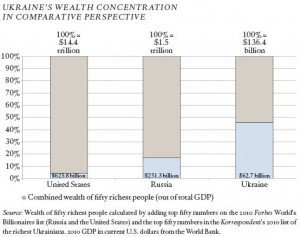

The oligarchs took everything. When the Soviet Union collapsed, a number of old party bosses made sure they took control of the biggest slices of the financial pie. Together with a handful of others, they created a caste of oligarchs, who completely dominate the Ukrainian economy. This is the same as happened in Russia, but the oligarchs have been even greedier in Ukraine. The fifty richest people in Ukraine own almost 50% of the wealth:

The political protests in Kiev stem from the serious economic situation, from people’s frustration with the decline in living standards and with widespread corruption, and from the people’s highly understandable anger towards the oligarchs.

But the protests are also rooted in Ukraine’s long historical tug-of-war between east and west. More people in the west of Ukraine collaborated with the German occupation forces during the Second World War than in the east. The so-called Ukrainian Liberation Army was established by Nazi Germany and fought together with the German forces against the Soviet Union.

The Nazist party Svoboda

These are the historical roots of the ‘social-national’ (read: Nazi) party Svoboda, which is currently playing a central role in the protests. A few years ago, this party was supported by less than 1% of the electorate, but they have been skilful at taking advantage of the crisis, rolling out a number of slogans appealing to general sympathies, including slogans against the oligarchs or slogans in favour of nationalisation and against corruption. The party leader, Oleh Tyahnybok claims that the party is  not fascist, but this is just an attempt to deceive gullible foreigners. The party’s first logo was the Wolfsangel rune (see right). The party’s chief ideologist, Yuriy Mykhalchyshyn, is an ardent follower of Joseph Goebbels who celebrates the Holocaust. He sees the Holocaust as ‘a bright period in European history’. The party is clearly anti-Semitic and talks of fighting the ‘Muscovite-Jewish’ mafia, not entirely unlike Hitler’s propaganda against ‘Jewish-Bolshevik plutocrats’. The party has added violence to its platform as a means of protest, and it uses terror against political opponents.

not fascist, but this is just an attempt to deceive gullible foreigners. The party’s first logo was the Wolfsangel rune (see right). The party’s chief ideologist, Yuriy Mykhalchyshyn, is an ardent follower of Joseph Goebbels who celebrates the Holocaust. He sees the Holocaust as ‘a bright period in European history’. The party is clearly anti-Semitic and talks of fighting the ‘Muscovite-Jewish’ mafia, not entirely unlike Hitler’s propaganda against ‘Jewish-Bolshevik plutocrats’. The party has added violence to its platform as a means of protest, and it uses terror against political opponents.

Svoboda’s real breakthrough came with the 2012 elections. It is now the largest party in three regions. On a national basis, they received over 10% of the vote (17% in Kiev), but in the city of Lviv and the surrounding districts they reached 31-38%.

Svoboda means ‘freedom’, but it is not freedom that the party is interested in. Their desire is to create an ethnically pure and dictatorial Ukraine. Representatives of the EU and of the West have acquitted themselves poorly by taking part in protests in Kiev together with this fascist party.

It’s easy to see how Svoboda’s policies, if they were carried out, could provoke war with Russia, and it’s not hard to imagine the EU and Germany being dragged into such a war either.

In steps China

Into this scenario of chaos – to put it mildly – there suddenly steps an all-new player, China. And it comes bearing what Ukraine is most interested in: capital and investments.

In 2012, China lent Ukraine 3 billion US dollars for the agriculture sector and 3.7 billion for the energy sector. As part of the deal, Ukraine will export 4 million tonnes of grain to China. In September 2013, Ukraine was offered a further 3 billion dollars from China to improve irrigation systems, with the aim of increasing grain production by 50%. This is presumably part of a broader arrangement in which China will buy 3 million hectares of agricultural land (an area slightly larger than that of Albania) from Ukraine.

Since the negotiations with the IMF on loan conditions reached an impasse, Ukraine has been desperately on the look-out for other loans. China has also been willing to act as a creditor.

In the middle of the mass protests in Kiev, President Yanukovych travelled to China to sign an agreement with the Chinese President Xi Jinping, reportedly securing investments in Ukraine from China worth approximately 8 billion dollars.

A drama of historical proportions is unfolding in one of Europe’s largest countries. ‘Ukraine has not yet died!’

[1] The lyrics were officially modified in 2003 so that the first line now translates as ‘Ukraine’s glory has not yet died’.

oss 100 kroner!

oss 100 kroner!