Globally, there is no longer any doubt that the economy is stagnating. The theory about the tendency of the economy to stagnate under monopoly capitalism has proven to be a very sustainable theory. The American Marxist journal Monthly Review has promoted this theory since the mid-1960s. The stagnation tendency is expressed partly by lower economic growth, lower employment, increased class divisions and less financial stability.

By Johan Petter Andresen, the leader of Grünerløkka No to the EU and a member of the Red Party.

This development has many political consequences. The major political battles within the EU and between the US/EU and Russia/China are central in this picture.

Before focusing on Great Britain, we’ll take a closer look at what distinguishes today’s capitalism from capitalism as it was when the EU encompassed fewer countries and was less integrated – i.e. the early 1970s.

Majority employed abroad

I use Norway as an example as I have good statistics at hand. The big change over the last 40 years is that the dominant monopolies have become considerably larger and much more internationalised. This applies to both the markets for the companies’ products and their production facilities. The largest companies now have the majority of their employees overseas. The thirty largest industrial conglomerates had only 6 percent of their workforce abroad in 1975 today the figure is 64 percent! The thirty largest enterprises had 59 per cent of their employment abroad in 2012, up from 48 percent in 1996 which was the first year with data for these figures. (The Productivity Commission’s first report from the spring of 2015, page 58.)

For these large internationalised companies it is critical to ensure as few obstacles as possible when selling their goods and services, organising their production across borders and ensuring the capital flow between all of their departments (including “mailbox” departments in tax havens). This is why the «system-bearing parties», i.e. parties both on the right and left, which see it as their duty to ensure the current capitalist system, have entered into international agreements that break down national barriers. Most free trade agreements must be seen in this light. This includes the WTO, TTP, TTIP, TISA, EU and the European Economic Area Agreement. Naturally, the geographical area and the scopes in terms of economic sectors vary, as do the degrees of cooperation. But the tendency is the same.

The EU goes much further than other intergovernmental agreements in the coordination of laws and regulations. The objective of creating an ever closer union is an attempt to create a European empire. But this is not possible without depriving the nation-states of power. Now, when the contradictions in the world intensify because of stagnation, this contradiction becomes clearer and the upper classes are divided. The most influential part of the upper classes continues to struggle for a superstate. The common currency the Euro, covers the countries which so far have gone furthest towards a superstate. This cooperation means that individual countries give greater power to joint bodies like the European Central Bank, European Commission etc. Not all EU countries have joined the Euro cooperation. This is due to two different forces. For Norway, it was the popular resistance that prevented EU membership and the Euro. The same applies for Sweden and Denmark. But for the UK, it appears that both popular forces and sections of finance capital have been against the introduction of the Euro. The UK opted out from the part of the Maastricht Treaty that concerns common currency in 1992. Yet there were strong forces that wanted Britain to join the Euro cooperation and the Tony Blair’s Labour government was preparing for a referendum on this question. In its program in 1997 Labour stated that a referendum on the Euro was essential if UK was to join the Euro. In 1999, the Euro was launched, but the UK did not join both because of popular resistance and because of opposition from sections of finance capital. UK is an old world power and has one of the world’s strongest financial centers. The Pound is a key international currency and is the third most used in the world. The US dollar is by far the most traded, followed by the Euro.

Superstate and nation-state

Thus, the upper class in the UK is divided when it comes to superstate or nation-state. The contradictions have led to the United Kingdom remaining outside the Euro and outside the Schengen Agreement. Growing dissatisfaction with the state of affairs after the financial crisis of 2008, and at the same time great progress for the right-wing populist anti-EU party, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), led David Cameron, the leader of the Conservative Party, in 2013, to pledge to renegotiate UK’s relationship with the EU if the conservatives won the election in 2015. Following these negotiations Cameron pledged he would hold a referendum before the end of 2017. The Conservatives won the election in 2015. In February 2016 consensus was reached on an agreement in the EU on UK’s demands. The most concrete point is that workers from poorer EU countrieswho come to the UK will get lesser social benefits in the first yearsof their stay. Otherwise the political declarations are of no particular importance. The agreement clarifies that some parts of the EU have made further progress in the attempt to create a superstate, while Britain is among the countries that are holding back because of internal disagreement, primarily within the upper classes.

Boris Johnson

Boris Johnson is a leading conservative politician and the Mayor of London. He is the main spokesman for Brexit among the conservatives and is mentioned in some quarters as potentially the country’s next prime minister. Johnson does not believe that Britain’s capitalists will benefit from being tied up in the EU in the future, as the EU is becoming increasingly centralised and is increasing supranational control over more and more central parts of the economy. The EU is currently strengthening control over the individual member states’ national budgets and fiscal policies. This will primarily affect the member states which have the Euro, but will also affect countries that do not have the Euro. Johnson also points out that the key growth regions in the world lie outside the EU and that the UK will be freer to invest in these countries and to enter into agreements with these countries while outside the EU. Against him stand, among others, those parts of the British capitalists that want to focus on strengthening EU-cooperation as a platform for UK capital’s international expansion in the future. They refer to the agreement that has recently been negotiated and believe that it can ensure that Britain’s capitalists have the necessary control.

The nation-state is most important

The contradiction between the facts that capitalism has created internationalised monopolies that need to secure their interests internationally on the one hand, and the fact that these monopolies rely on the nation-state for their essential security, cannot be resolved within the capitalist system. When the British monopoly Arcadia Group’s interests must be defended, the main state-construction is not the EU but the nation-state. It is the nation-state that can make laws that protect monopolies’ interests in relation to its own population and protect them against monopolies with their base in other imperialist countries. And as «creditor of last resort» the tax authorities in each nation-state can «socialise» financial losses, as we experienced in connection with the financial crisis of 2008. The state will solve a new banking crisis through more taxes for ordinary people and tightening government budgets. It is the individual nation-state that determines how much power it will hand over to the EU system and that ultimately can break out of the EU either as a result of what this country’s ruling class decides, or as a result of popular struggle, or, as in the case of the UK, as a result of a mixture of forces involving the upper class and popular movements.

The people and the nation-state

Another aspect of the relationship between the EU and the nation-states, is that it is within the nation-states that the popular forces have gained ground. The working class struggle is international, but it is within the nation-state framework that popular movements have gained ground in the fight for democratic rights, nationwide collective agreements, local democracy, welfare etc. The international conventions, such as the European Convention on Human Rights from 1950, preceded the EU and are, naturally not a result of efforts by the EU, but of the strengthened position of the working class in Europe after World War II. The EU’s supranational laws and the European Court have been used to undermine trade unions’ influence and other popular organisations’ influence in the individual nation-state and to undermine the welfare state.

More and more people in the EU and the EEA are turning against the EU. Therefore, EU-sceptical parties and organisations have emerged and have grown. But exactly because the monopolies and the popular forces both have an interest in defending the nation-states, both right-wing populist and left-wing populist movements that effectively ensure the interests of capital, arise. They capture the popular discontent and ensure policies in line with the interests of the internationalised monopolies. This is what the UKIP and Labour under Jeremy Corbyn have in common, despite UKIP being against EU membership and Labour wanting to remain in the EU. If we look elsewhere in Europe, we see the same phenomenon. The left-wing populist parties have the same objective, such as SYRIZA and PODEMOS. These two want a «Social Europe». At the EU level, we find these two cooperating in the European Parliament in the red/green faction consisting mainly of pro-EU parties, but where we also find a minority of parties that are against EU membership. An attempt to strengthen EU reformists was initiated the former finance minister of Greece, Yanis Varoufakis this spring. The new pan-European umbrella organisation DiEM25 aims to reform the EU by 2025. However, the DiEM25’s aims do not contain crucial reforms of any value. For more on DiEM25 read the article by Pål Steigan.

Sadly, what is striking is that there are not many broad popular united fronts aimed against both EU-membership and against the neoliberal austerity policies in their own nation-state.

In the UK we see an alignment of forces roughly in line with the above analysis. On the «remain» side we find the employers’ organisations, the Conservatives, Labour, Sinn Fein, Scottish National Party, the Welsh Plaid Cymru and the leadership of the TUC, the bulk of the country’s elite. On the other side we find the UKIP, some smaller unions, a minority in Labour and a larger minority among the Conservatives.

British characteristics

A notable feature of the parliamentary system in the UK is the “first past the post” electoral system. In 2015, this meant that the UKIP, which got 3.8 million votes, 12.7 percent, gained only one Member of Parliament out of 650. But another aspect is what we in Norway call “the political centre” usually ends up in one of the two big parties, and as far as I can understand, more commonly in the conservatives. In Norway, the Conservative Party is an urban party. In Britain the Conservative Party is strong in the countryside. This means that popular discontent can be expressed as discontent among Conservatives.

Many EU opponents got their hopes up for Labour, the second largest party in the UK when Jeremy Corbyn was elected as its new leader. But it only took a short time before Corbyn, who previously has been against both EU membership and the Maastricht Treaty, made an “about turn” and aligned with those wanting EU reform.

Sinn Fein, SNP and PC

The left populist Sinn Fein is a party that has been central in the struggle against the austerity policies of the EU and the government of Ireland. Sinn Fein has mobilised against various EU treaties that have been voted on in Ireland, like the Treaty of Nice, but not as a part of the struggle against EU membership, but as part of the struggle for a more democratic EU. They have lost these battles and the EU has become increasingly similar to a superstate. Still, the Sinn Fein does not draw the conclusion that Ireland must leave, they cling to the hope that the EU can be reformed to a “Social Europe”. Sinn Fein is also represented in Northern Ireland’s parliament. In connection with the EU referendum the Sinn Fein’s leadership refers to the Long Friday Agreement of 1998. The Long Friday Agreement was the «peace agreement» which introduced a certain degree of self-determination in Northern Ireland. Sinn Fein claims that the Long Friday agreement has rules meaning that a Brexit would lead to a situation where a referendum concerning the unification of Ireland and Northern Ireland would be required. Sinn Fein also claims that such a united Ireland will be a member of the EU, like Ireland is today. Sinn Fein urges people in Northern Ireland to vote to remain in the EU. Thus, Sinn Fein does not aim for a sovereign united Ireland.

The Scottish National Party is also to the left of Labour and has been the largest party fighting for Scottish independence from the rest of the United Kingdom. They are now Scotland’s biggest party. This party also wants to remain in the EU.

Plaid Cymru in Wales is for independence from England/Westminster, but is in favour of EU membership.

All these left populist parties are «system-bearing parties» who primarily see it as their task to secure capitalism in their respective areas. The part of the bourgeoisie which they represent, want greater power within the UK and want to use the EU to forward their international interests. As pointed out above, these parties also have the important function of capturing popular discontent and giving it expression within the system.

Thatcher

To complicate the picture even further, we must look at the latest history of relations between the UK and the EU and the internal class struggle in the UK. In short, we can say that the UK’s upper classes were among those who had the toughest approach in their attack on trade unions, when the bourgeoisie on an international scale initiated the neoliberal wave at the end of the 1970s. This culminated during the miners’ strike in 1984, where the Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher won a crushing victory and imposed new anti-union legislation. The Labour Party did not aim to reverse this. On the contrary Tony Blair, Labour prime minister for many years, made only minor changes to the anti-union laws. One of the consequences of this onslaught is that the class differences in the UK are among the biggest in the OECD. The fact that Thatcher made a considerably more vicious assault than most EU countries and the EU itself, lead to EU rules being perceived as a hedge against the labour movement’s position getting even worse. The EU holds the UK back, said representatives from one of the largest trade unions, UNITE, during a meeting with a No to the EU Delegation in January 2016. But it is precisely the EU that is a formidable force for anti-worker and anti-trade union policies in member countries. This is perhaps best illustrated in Greece, where legislation that undermines the working class and the labour movement’s position was implemented according to orders by the EU and the IMF. The apparent disagreement between the EU and the conservative government over the intensity of anti-worker policies hides the fact that both of them are pulling in the same direction, be it with different methods and different forms. For a trade union movement that wants to attempt an offensive against the bourgeois politics, it is quite obvious that this will be easier if it is only the British government and bourgeoisie that is the formal counterpart, rather than having also to take on the EU system.

Against the EU and against austerity

Among the political forces that want to leave the EU, there are also forces that are more akin to what may be perceived as the positions of the Norwegian organisation No to the EU. This applies to the medium large union the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers (RMT), the organisation Trade Unionists against the EU, Campaign against Euro-federalism and a minority in Labour organised in Labour Leave. These are the main forces that are part of a popular movement against the crisis policies of both the EU and the UK government. But these forces are weak and do not constitute the strongest voices on the «leave» side.

There are some parties that call themselves communist like the Communist Party of Britain . The Communist Party of Britain (Marxist-Leninist) and the Communist Party of Great Britain (Marxist-Leninist). These three micro parties mobilise for Brexit. While, for example, the revolutionary weekly paper The Worker is for an «active boycott» and believes that the coming referendum is meaningless.

Controlled referendum

Britain has a special commission which has the authority to designate an official campaign organisation for each side in connection with the referendum. All indications are that a «leave» campaign organisation dominated by right-wing populists will be appointed in mid-April. This organisation will be the one representing the «leave» side in central televised debates, will have greater financial muscles and will have the opportunity to distribute its views to all households etc.

At the present there are two campaign organisations that have the best odds to be appointed. These are Vote Leave and Grassroots Out (GO). Whichever of the two is appointed, the conservative forces will dominate in the leave campaign along with the right wing populist UKIP.

Leave can win

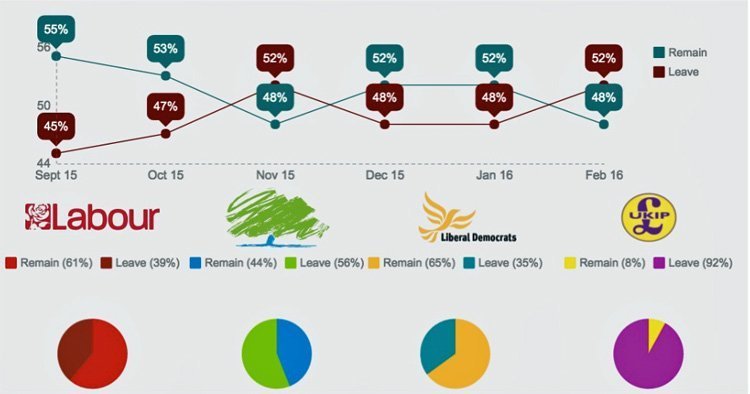

Polls show at present a slight lead for the remain-side. But the outcome is not given. Democracy will benefit if there is a majority vote to leave the EU in the referendum on the 23rd of June. The EU will be weakened and opportunities for increased popular influence in Europe will increase. But the future struggle will regardless not be easy.

If there is a majority to leave the EU, there will be negotiations for a couple of years between the EU and the UK on agreements that would replace membership. The leave side has not given a clear picture as to which solutions it wants. There are many options, these include an agreement similar to the EEA Agreement; a free trade agreement without the free movement of services and labour; a British re-entry into EFTA and a renegotiation of the EEA Agreement, etc. As there are «system bearing parties» negotiating on both sides of the table, we must assume that there will not be a political earthquake.

Scotland, Ireland and Wales

But in Scotland, Ireland and Wales a new situation can arise where demands for referendums on secession from the United Kingdom will increase. The Scottish National Party (SNP) has already said that the force behind the demand for a new referendum on Scottish independence will be strengthened if there is a Brexit. But even if there is a majority for the UK to continue in the EU, the SNP take this as evidence that the Scots want independence from Britain. In particular, they will argue point, if there is a majority in England against EU membership, while there is a majority for EU membership in Scotland. Those who are fighting for Scottish independence have good winds behind them almost regardless of the result. In Ireland, Sinn Fein could demand a referendum on unification of Northern Ireland and Ireland. But a reunion will only be realised if there is a majority for this among the people of Northern Ireland, which is unlikely. In Wales the demand for independence will also be strengthened. The question of a possible dissolution of the United Kingdom will not be determined until one or more new agreements are in place between the EU and the UK. Therefore it is not possible to say how individual parties will act over the next period.

A possible breakup of the United Kingdom into four independent nation-states: England, Wales, Scotland and a united Ireland, will be a positive step forward for both self-determination and democracy. But self-determination will be undermined if three of these same nation-states subject themselves to a new union and partake in the construction of the European superstate. A possible liberation from the UK, but continued integration into the EU will lead to new political movements that will struggle against this union. We will at the best see a united front which targets both neoliberalism and the EU, or, worse, a new movement demanding independence from the bureaucrats in the EU, i.e. a rightist populist party.

Domes Day Prophecies

The remain-side is hammering on the same “doom and gloom” prophesies that have been used in the past. And we know them all too well from Norway: If the UK leaves the EU, investments will disappear, firms will leave the UK and move to the EU, jobs will disappear, Britain will be isolated etc.

Naturally, this will not happen. The crisis of overproduction, stagnation and increasing unemployment will affect all countries that do not break away from the capitalism of today. Continued neoliberal politics will influence countries both in and outside the EU, as «system-bearing» parties are still in control. The possibility for the working class to defend itself will be greater outside the EU, as political campaigns etc. take place on the basis of common experience and a common understanding of reality. It is farto go to London but even further to Brussels. The working class struggle is international also in the future, but it is precisely the struggle in the individual nation-state that is the most important arena for the struggle for democratic rights, better pay and working conditions and defense of the welfare state.

—

And I have translated this article to English, precisely because the struggle is international.

oss 100 kroner!

oss 100 kroner!