Are you familiar with the Global Redesign Initiative (GRI)? Probably not, unless you’ve been following steigan.no a good while. Mainstream media have been fairly quiet about it. So what is GRI, really? It is exactly what the name implies: An initiative to restructure the entire global system which institutionalizes cooperation among countries, international cooperation and conflict resolution. That is: International law, security, disarmament, war and peace, international economy and trade, climate and environment, poverty and equalization, human rights and a number of other issues.

Translated by Anne Merethe Erstad

This international order originates from the Peace of Westphalia back in 1648; the treaties that ended the Thirty Years’ War and established systems of political order among sovereign and independent states. And this order has, essentially, been operative ever since.

In order to replace this more than 350 years old order with a new system, in which transnational corporations are granted equal – or even superior – footing with representatives of nation-states in matters of international agreements and institutions, the World Economic Forum (WEF) has chosen GRI as its instrument. The Forum wants to “redefine the international system as constituting a wider, multifaceted system of global cooperation in which intergovernmental legal frameworks and institutions are embedded as a core, but not the sole and sometimes not the most crucial, component”. This is repeated again and again throughout WEF’s documents, especially in the 604 pages long rapport about GRI, which is the source of this quote here. If you want a five minutes brief version, you can enjoy this video with Harris Gleckman.

There is absolutely no doubt what WEF wants. Official documents state it, straight out. It aims for political power through new international executive bodies where The Forum is not just equal to nation-states but in many cases superior. The Canadian Don Tapscott, a well-known economic analyst and a member of WEF is one who puts it plainly:

“To achieve new models for global problem-solving we have to overcome a major obstacle: The world is organized around nation states based on national economies and that is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future.”

What is World Economic Forum?

Read that last quote one more time. To whom and to what are the nation-states and their national economies an obstacle? Tapscott speaks on behalf of WEF. So, what is WEF and whom does this organization represent?

In the media, World Economic Forum is best known for its annual winter meeting in Davos. It’s a “society” composed by 1000 member companies, typically global enterprises with more than five billion dollars in turnover. These enterprises rank among the world’s top companies within their field; corporations, banks and financial giants. Its 100 strategic partners include companies like BlackRock, BP, Facebook, Goldman Sachs, GM, JPMorgan Chase, Microsoft, Nestlé and Rockefeller Foundation. The total economic strength of the WEF members can only be measured in thousands of billions of dollars.

This is the Global Redesign Initiative

According to the World Economic Forum, «the current framework of global governance is as much the problem as the solution». The quote can be found in a brief summary explaining the GRI. And in fact, they’re right.

Truth be told, the system has failed to solve any of the huge, global problems the world is facing. According to WEF, it worked tolerably well prior to the financial crisis of 2008, but (it) has lacked the ability to handle any of the extensive global crises ever since. The current system lacks legitimacy and strength, WEF claims; and this situation is so grave, action must be taken. Even economic growth, the foremost sign of the capitalist economic system and a fundamental premise of preventing its breakdown, is hardly upheld by the system at the moment.

WEF intends to change this. The Forum refers to GRI as “A visionary blueprint for meeting the challenges of the 21st century” in the short summary of “Everybody’s business: Strengthening International Cooperation in a More Interdependent World”; a 604 pages long rapport compiled by the World Economic Forum in 2010. According to WEF, this is the problem:

Today’s world is characterized by a power shift from North to South, from West to East. This power shift is not reflected in the institutions that were organized following World War II. In addition, the world has become far more complex and bottom-up than top-down. Thus, facing critical, global challenges, the traditional negotiation processes, which are characterized by a defense of national interests, are no longer sufficient.

The global financial and economic crisis has demonstrated that the international community needs to engage in a fundamental debate on the structures of cooperation by which it is governed, WEF goes on. Many global institutions and cooperative arrangements need to be updated or upgraded to address three fundamental problems: global markets fail, sovereign states fail and intergovernmental institutions fail. “All three points reflect failures of imagination, political will and, in particular, an unwillingness to rethink the foundations of international order”, if we are to believe the WEF.

Nation states and intergovernmental structures are still to play a role in global decision-making, but those institutions need to begin more clearly to see themselves as just parts of the wider global cooperation system that the world needs. Also, they should work explicitly to cultivate such a system by anchoring their decisions more deeply in the processes of interaction with interdisciplinary and “multistakeholder” networks of relevant experts and actors.

“Traditional conceptions of global governance require rethinking. Deepened global cooperation along current lines is necessary but not sufficient. (…) Our intergovernmental institutions and processes must be embedded into wider processes and networks that permit scaled and continuous interaction among all stakeholders and sources of expertise in global society in the search for solutions.”

If you find this hard to make sense of, a small consolation is that the original is worse. But such is the language of WEF. Still, they make themselves clear. They don’t conceal their opinion or their purpose.

The transnational corporations, the mega banks and the financial magnates no longer accept to be excluded from the traditional system of global governance which builds on the nation-states and the international UN institutions. They want to be part of the decision-making, and they want to provide the guidelines for this to happen. Consequently, they want to push the institutions elected by the people, the democratic establishment, to the sideline without cutting them off altogether. They will still play a part, but in a new, far more extensive system where the transnational corporations and the forces of capital – by their own will and based on their own interests – shall govern as equal partners to parliaments, nation-states and the international, intergovernmental institutions.

And who is, in WEF’s opinion, the most suited to develop this new, global governance system? The WEF itself, of course!

The fact that WEF does not ask why the current international systems fail to function, is striking, and somehow reveals the analysis as rather shallow. Could the reason be that the transnational corporations and their owners, who have the better part of the world’s capital at their disposal, make their dispositions entirely outside of democratic control and also, by lobbying and via other direct or indirect channels actually have a great deal of influence on “democratic” decisions – with one goal only: to secure financial profit?

Of course, the way the system works, neither parliaments nor governments could make serious attempts to break free of it. What might replace it? No current alternative exists. And even if it did, any determination to ally with the (masses of) people in order to introduce it is hard to find among politicians. “When in Rome, do as the Romans”, seems far more convenient.

Two central WEF concepts are «stakeholder» (or “multi-stakeholder”) and “governance”

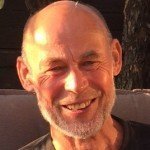

The word “stakeholder” is known in gambling as a person entrusted with the stakes of bettors, e.g. in horse racing. The stakeholder theory is a field of its own in management theories, and in the business world a stakeholder is a person, a group or a business that has an investment, a share or an interest in an enterprise. (However, the nature of a stakeholder is highly contested, and there are numerous definitions in the academic literature.) As the saying goes: A picture is worth a thousand words, so here it is; WEFs illustration from “A Partner in Shaping History”; the story of the first 40 years after WEF was founded, as the WEF sees it.

Every corporation has its stakeholders, represented by a circle in the circumference, with the corporation in the center of the figure. Multi-stakeholder then means, still according to WEF – the group of all stakeholders. The figure expresses three central elements in WEF’s way of thinking. Multi-stakeholder structures do not mean that all stakeholders are equally important; the corporation plays the most central part in the process and WEFs multi-stakeholders are first and foremost those who have commercial ties to the corporation: customers, creditors, suppliers, collaborators, owners (shareholders) and the national economy. All other conceivable stakeholders are placed inside a circle named “government and society”.

The very core of WEFs stance can be expressed by their introduction of the term “multi-stakeholder governance”. In this context governance does not refer to a government, but relates to management. So, not governments but the corporations with their multi-stakeholders should be the governors.

When the WEF was founded in 1971, Klaus Schwab, the founder and leader of the WEF, proposed that “management of the modern enterprise must serve all stakeholders acting as their trustee charged with achieving the long-term sustained growth and prosperity of the company”. (The World Economic Forum: A Partner in Shaping History. The First 40 Years).

Note the purpose here: The main issue is the company’s own, long-term interests. The consequence of this way of thinking is that the corporations must assume social responsibility. Well and good, you might think. But they want to assume social responsibility their own way. Not by preventing ruthless exploitation of people and natural resources, not by putting a stop to pollution or tax dodging, not by enter into wage agreements and see to safe working and employment conditions, take care of vital social needs etc. No, they demand a seat at the table where the decisions are made, to look after their own interests.

So, how do we define governance in this setting? I define it as command, as this isn’t a question of establishing an institution which offers views and opinions, but one that actually executes power, makes decisions and, moreover, is able to implement its policy simply by the immense economic force of the leading transnational corporations. As we know, these corporations form the core of WEF. They are the ones with sufficient strength to take the lead in the kind of institutions WEF wants to create.

In her book Shadow Sovereigns – “How Global Corporations are seizing Power” (Polity Press, Cambridge, 2015) Susan George wrote: “Governance is the art of governing without government.” To exemplify she points to the daily business of the European Commission. It answers to no democratically elected assembly.

The international system pictured by WEF differs fundamentally from the current international order of international treaties and agreements as well as the institutions based on UN member states, where the non-governmental corporations and organizations have to be content with attempting to influence the system from the outside.

Instead, WEF wants an order where the corporations or nation-states who acknowledge a problem gather and involve those they want to include (other states, corporations or international organizations) – and do not wait for a formal authorization or mandate to start. In this system the nation-state organizations are no longer supreme actors, they have accept sharing the leading place or perhaps even be content with second or third.

A board member of Transnational Institute (TNI), the writer David Sogge, gives the following comment on the WEF plans:

“It is not hard to see the myriad dangers of this approach. Rolling back state authority while private bodies carry no real liabilities for consequences of their neglect or mismanagement will turn today’s accountability gap into a yawning abyss. Replacing democratic systems with stakeholder systems raises serious questions about representation and who is chosen to represent us. Substituting enforceable laws with voluntary codes of conduct introduces capricious ad-hoc ways of making rules and enforcing them. Given the public’s declining trust in today’s governance, already in thrall to private interests, WEF’s vision is hardly propitious for a stable public order that everyone, including business, needs.

The real danger of WEF’s proposal, though, is that its design has already passed from drawing boards to routine practices in many realms of our life, including health, nature conservation, trade, security, and digital rights. UN institutions have adopted corporations as leading partners, chiefly under terms of its UN Global Compact. It is seen in workings of the World Water Council or in Food-Water-Energy nexus summits where corporations are both the hosts and driving participants while governments and civil society take back seats. It is also evident in the many international boards and regulatory agencies that set standards and rules for specific industries which are either toothless or captured by the very corporations they seek to regulate.”

More specific, in his rapport «Multi-stakeholderism: a corporate push for a new form of global governance”, Harry Gleckman at TNI lists a number of critical questions regarding the idea of multi-stakeholders ruling the world. How are the categories of actors selected or excluded? How to address the power balance between the actors? Who decides the internal decision-making process for the multi-stakeholder groups? Who finances them? What are their obligations to the international society? To whom do they answer? Who defines and limits the areas of responsibility?

The answer to all of these questions is that there are no guidelines. For instance: The multilateral international system based on nation-states requires the member states’ governments to appoint representatives who can vote, bring forth a proposal etc. A similar system for the multi-stakeholder groups does not exist. The UN system provides guidelines for the economic contribution required from each member state. When such guidelines don’t exist for multi-stakeholder groups, many organizations and countries will be excluded simply by economic reasons.

Obviously, the consequence of all these uncertainties may very well end up in “might makes right” – the transnational corporations holding the greatest economic power and the largest imperialistic countries get to rule. These are the ones who get to decide who will be involved, the ones to determine guidelines, goals, standards and regulations, all of which is essential to them.

In her book “Shadow Sovereigns” Susan George writes:

“All the wrangling over the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership shows that the issues of standards, norms and regulations are crucial for business. Seen from Brussels, Washington and executive suites on both continents, they are not necessary protections for health, safety and the environment, but ‘obstacles to trade’.”

She also describes how the transnational corporations have worked for years to establish TTIP, partly in order to handle just this.

Global Redesign Initiative breaks “the power stems from the people” principle

When a large international organization of the most powerful capital forces in the world openly launches a program to deprive the nation-states, the parliaments and the governments of power and influence, one would expect loud and forceful protests from the politicians. But the world doesn’t work that way. On the contrary, leaving aside a few exceptions, we don’t hear as much as a squeak from “responsible” politicians.

One might ask why? Of course, for some, their political loyalties lean this way. Others are trapped in the system and forced to play by the rules. Some may realize it, but they are just as aware that in order to uphold the impression of possessing political power which provides a purpose for asking people to vote for them, they need to keep “doing as the Romans” and be content to act within the scope of action they’re granted.

Anyhow, politicians outdo each other renouncing authority and control. (A decent exception is the parliament of Uruguay. This winter they quit the TISA negotiations.) In Norway, both The Conservative and The Labour party – along with several smaller parties – are hearty supporters of EU, EEA, TISA and TTIP, and gladly renounce decision-making authority to international institutions as well as multinational corporations operating outside the range of democratic control. In fact, it’s quite strange. Generally, politics is all about seeking power and exercising power. But the prevailing policy in today’s neoliberal era is to sign away power to transnational corporations, the mega sized banks and the 0,001 percent richest people in the world.

These actions by Norwegian politicians are irresponsible. They do not administer their responsibilities according to the Constitution of Norway. The Constitution holds them answerable to the people of Norway and the politicians have no right to sign away the authority granted them by the Constitution. This is clearly stated in Article 49: “The people exercise the Legislative Power through the Storting” (the parliament). So, when politicians now want to subject Norwegian financial supervisory authority to the EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA) in Brussels, they disrespect our Constitution.

Corresponding provisions can be found in the constitutions of many countries. Some examples:

USA: We, the People of the United States (…) establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

Sweden: All public power in Sweden proceeds from the people.

Italy: Sovereignty belongs to the people, which exercises it in the forms and within the limits of the Constitution.

Russia: The multinational people of the Russian Federation shall be the vehicle of sovereignty and the only source of power in the Russian Federation.

France: The motto of the Republic shall be «Liberty, Equality, Fraternity». Its principle shall be: government of the people, by the people and for the people. National sovereignty shall belong to the people, who shall exercise it through their representatives and by means of referendum.

These formulations aren’t just old empty phrases from days long gone by. The Italian constitution dates from 1947 and the Russian from 1993. Equivalent wording can be found in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 21: The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government.

In countries with constitutional legislation like these, the politicians have no right to sign away national authority, because they merely administer the power on behalf of the people. The people must continue to have the right to reclaim that power. Shouldn’t our politicians have objected to WEFs offensive to undermine democracy and representative government? The fact that this is nevertheless happening , in a growing number of areas, goes to show that the huge transnational capital forces have the governments and the state authorities in their pocket – whether the latter are aware of it or not.

An ordinary member of parliament may have an excuse. Most likely, they have no idea what they’re taking part in. But political party leaders like Jonas Gahr Støre (Labour) and Prime Minister Erna Solberg (Conservative) have no excuses. They must be expected to know what they are doing. However, this makes it easier to understand why the Norwegian political elite and the major media keep quiet and apparently don’t mind the ignorance of the average Norwegian in regard to where the power ends up.

The process is in motion

GRI manifests a coordinated neoliberal, global offensive by the most powerful capital forces in the world to deprive the nation-states and their democratic institutions of power. For the benefit of whom? For the transnational structures as well as the international organizations and institutions where the forces represented by WEF have conclusive influence. In his memo “A Global Post-democratic Order”, Leigh Phillips at the Transnational Institute describes EU as an altogether neoliberal project to secure the interests of the large corporations and financial institutions. He writes that EU is “a blueprint for post-democratic governance around the world, at the global, continental, national, and even local level”. (TNI State of Power 2016, p. 39)

The Lisbon Treaty, which forms the constitutional basis of EU as a political and monetary union, offers many splendid words on democracy and personal rights, but Article 3 also states: “The Union shall establish an internal market. It shall work for the sustainable development of Europe based on balanced economic growth and price stability, a highly competitive social market economy…” And what is the internal marked about? “The internal market shall comprise an area without internal frontiers in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is ensured in accordance with the provisions of the Treaties.”

But where do the private corporations and the financial institutions enter the picture? Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO) is an independent research and campaign group working to expose and challenge the business sector’s EU lobbying. According to CEO there are 15.000 – 30.000 lobbyists active in Brussels. Two out of three work for the business sector and their annual budget exceeds one billion euro by far. This ranks Brussels second only to Washington DC among the largest lobbyist centers in the world.

Leigh Phillips quotes the Polish sociologist Zygmunt Bauman:

“The wedding between power and politics that was signed in Westphalia has been annulled. While politics (the ability to decide which things ought to be done) is confined to the level of the nation-state, power (the ability to get things done) has shifted to a supra-national level. This has resulted in a crisis of agency: States are entangled in international networks and lose their sovereignty, while global markets are cut off from any guidance and supervision.”

In her book “Shadow Sovereigns”, Susan George describes how transnational corporations infiltrate several UN institutions.

The arrangement for settlement of dispute ISDS and public-private cooperation

ISDS (Investor-state Dispute Settlement) is contained in several thousand bilateral and multilateral agreements, such as TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) and NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement), and is likely to be contained (in some form or other) in TTIP (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership). ISDS grants an investor the right to sue a foreign government in case the government introduces regulations that inflict on the investor’s economic interests. The proceedings will not be held before the country’s court of law or according to the country’s legislation. Instead, the company shall bring the dispute to an arbitration tribunal, where three arbitrators will decide on the matter.

The nation-states, on the other hand, have no equivalent rights in case they want to hold companies responsible for damages or expenses they may cause the people or the country. In the TTIP negotiations the European Commission has suggested an alternative arrangement called Investment Court System which supposedly avoids the worst effects of ISDS. There’s every reason to doubt that is actually the case.

Public-private partnership (PPP) is an important instrument in GRI. It’s mentioned at least 160 times in WEFs 604 pages long report. Our Norwegian “blue-blue” government is an enthusiastic supporter of PPP.

Daphne T. Greenwood, professor of economics and director of the Colorado Center for Policy Studies at the University of Colorado, has carried out an extensive analysis of PPP in USA and concludes that outsourcing to private corporations undermines the democratic system; it often has a negative effect on working conditions and service provision; it does not always lead to improved efficiency or quality; and tax money end up in private pockets. And last, but not least, possible cost savings due to PPP are often achieved at the expense of reduced wages and benefits for workers.

Similar conclusions are known from several European and Scandinavian analyses, for instance this report from Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU), University of Greenwich. On behalf of the Norwegian “Fagforbundet” (The Norwegian Union of Municipal and General Employees), Hallvard Bakke, former minister of trade in Norway, has compiled a report where he concludes that: “experiences both in Norway and abroad show that PPP projects end up with higher costs than projects run under public sector auspices” and refers to the Cameron government in UK cancelling all new PPP projects due to the experience that they are a waste of public funds. The alternative to PPP is to reinforce the democratic processes, open up to user involvement, grant the employees more responsibility and co-determination and strengthen public ownership and funding.

This is how the Norwegian mainstream media present GRI

Basically, GRI is a nonexistent topic in the established media in Norway. I find nothing in The Norwegian Broadcasting System (NRK), or in “Bergens Tidende”. “Klassekampen” has published a handful of articles in 2016 about Word Economic Forum, but nothing about GRI.

The few short pieces that have been written give the impression that GRI is a fairly nonpolitical affair intending to improve the world. A person actively promoting this view is the Crown Prince Haakon of Norway, who has been a member of the foundation board of The Forum of Young Global Leaders since the fall of 2010. According to kongehuset.no (The Royal House of Norway’s homepage) “Young Global Leaders” is the most important voice of the young within the World Economic Forum. The objective of GRI is “to arrive at concrete solutions which will enhance the international society’s ability to solve major global challenges”; again; according to the same homepage. Yes, something like that is stated in WEFs own presentation of GRI, subtitled “A visionary blueprint for meeting the challenges of the 21st century”.

The newspaper «Aftenposten» follows up. October 12.th 2011 the story “Leder fattigdomskamp fra Slottet” (Fights poverty from the palace) goes: “A year ago the Crown Prince was assigned a central part in a new initiative by the World Economic Forum founder Klaus Schwab: Global Redesign Initiative. The forum is to present ideas and suggestions to enhance global equalization and fight poverty.” The story describes GRI as a “brainstorming launched by World Economic Forum to create a better world”.

Join forces with Goldman Sachs, BlackRock, Nestlé and other multi-billion corporations to fight poverty… Supposedly The Royal House and “Aftenposten” hope the readers will believe such an idealized depiction of GRI. It is conspicuous, since WEF doesn’t make any attempt to hide what GRI is all about. It is repeatedly stated in the WEF documents. This isn’t a matter of changing a few organizational structures and methods. This is a matter of changing the entire way of thinking in regard to international relations and governing (WEFs GRI report, p. 9):

“The time has come for a new stakeholder paradigm of international governance analogous to that embodied in the stakeholder theory of corporate governance on which the World Economic Forum itself was founded. (…)The state-based core of the system needs to be adapted to a more complex, bottom-up world in which nongovernmental actors have become a more significant force.”

A paradigm is a mode of thought, a set of thought patterns on which an entire set of theories and concepts rest. “The power stems from the people and is exercised by the nation-states” is a paradigm WEF wants to replace with a new paradigm, namely: “multi-stakeholder governance”, which in the real world will appear as a paradigm where the small group of people controlling the transnational corporations and the mega sized banks, will hold more power than all of the world’s governments and national assemblies.

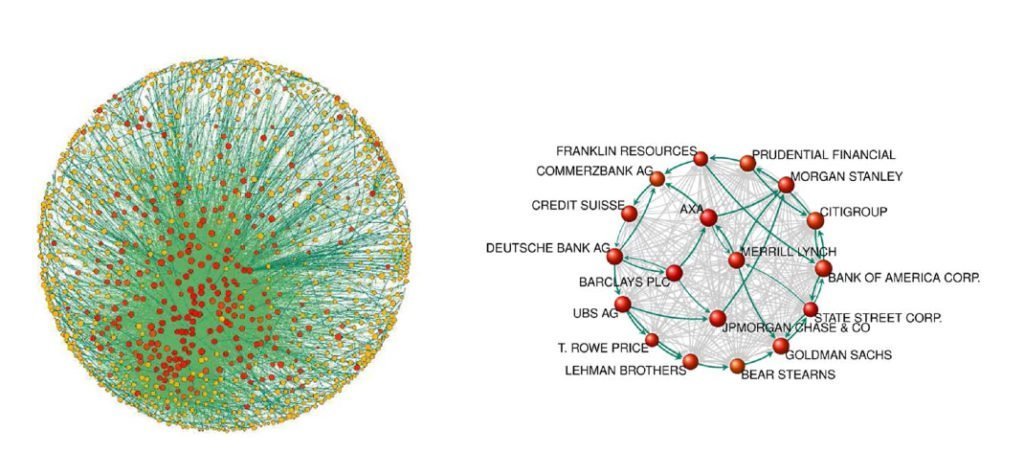

Vitali, Glattfelder and Battiston at ETH Zürich have analyzed the network of transnational corporations. Their 2011 article is freely available for anyone to read. They discovered that “nearly 4/10 of the control over the economic value of TNCs in the world is held, via a complicated web of ownership relations, by a group of 147 TNCs in the core, which has almost full control over itself.”

A list of the 50 most significant transnational corporations you can find here. Among the 30 most significant, eleven are also among WEFs 100 Strategic Partners.

The paradigm shift is already happening, but apparently, people in Norway are not supposed to learn about it. The established media neglect their duty to inform the public of significant political circumstances, which is one of the conditions for a living democracy. In Norway the media is often referred to as the fourth estate, inferred as a free and independent critic and source of information. The mainstream media may be independent of the state, but they are controlled by the most powerful capital forces. Even our domestic Schibsted is controlled by the largest financial forces in USA.

Based on this, it would be tempting to say that WEF expresses the desire of high finances to take over the role as the fourth estate. But that would be false. It is the role as the first branch of government they want, and they have presented a plan of how to conquer it. Our domestic politicians obviously find that quite all right. The Crown Prince Haakon of Norway is not very likely to end up as a crown prince for the new first branch of government. The crown prince Espen Barth Eide of Jonas Gahr Støre (current leader of the Norwegian Labour Party) has better chances. He is WEFs Head of Geopolitical Affairs and member of the Managing Board. Which probably says more about the Norwegian Labour Party than the World Economic Forum.

oss 100 kroner!

oss 100 kroner!