Den amerikanske finansbanken JPMorgan Chase er en av verdens største banker. Den har enorm innflytelse både politisk og økonomisk og tilhører den innerste kjernen i USAs og Vesten kapitalisme. I 2013 publiserte banken et notat der den drøftet Europas økonomiske og politiske problemer. Det kan være svært nyttig å lese notatet i lys av den akutte krisa i Hellas. For i likhet med Tysklands finansminister Wolfgang Schäuble mener JPMorgan at det er nødvendig med alvorlige økonomiske kriser for «å skape en narrativ for politisk forandring».

Notatet har tittelen The Euro area adjustment: about halfway there.

JPMorgan mener at euroen har innebygde svakheter på grunn av de nasjonale motsetningene i Europa. Det er det jo lett å si seg enig i. Men JPM mener at disse motestningene må løses ved å bryte ned den nasjonale motstanden og sørge for mer autoritære regimer.

The political systems in the periphery were established in the aftermath of dictatorship, and were defined by that experience. Constitutions tend to show a strong socialist influence, reflecting the political strength that left-wing parties gained after the defeat of fascism.

“Political systems around the periphery typically display several of the following features: weak executives; weak central states relative to regions; constitutional protection of labour rights; consensus-building systems which foster political clientalism; and the right to protest if unwelcome changes are made to the political status quo. The shortcomings of this political legacy have been revealed by the crisis.

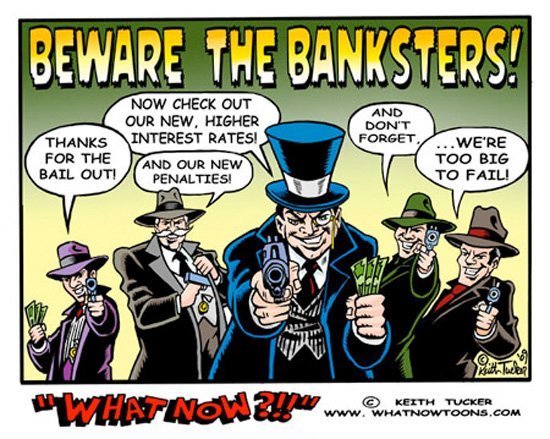

Det er mye å si om JPMs historieskriving. Det har ikke vært mye sosialistisk tankegods i det politiske systemet i Sør-Europa. Men det har vært et klassekompromiss der kapitalen for å få ro har gitt arbeiderklassen en del sosiale og politiske reformer. Men nå ser banksterne i JPM disse lommene av demokratiske og sosiale rettigheter som vesentlige hindringer for sin profittmaksimering i Europa. Derfor må de bort. Men hvordan oppnå det?

Svaret JPM gir er å utnytte krisa: «It is not possible to develop a macro story for the Euro area without having a narrative of crisis management.»

A crucial final question is what will prompt Germany to agree to a new narrative — essentially greater risk/burden sharing at the regional level. In our view, there are two ways this could happen: first, when significant progress has been achieved in the national adjustments; or second, if there is an irresistible build-up of political and social pressure around the periphery.

Det vi tränger på kort sikt er en fiskalunion. I en større kontekst tränger naturligtvis en politisk union.

He sees the turmoil as not an obstacle but a necessity. “We can only achieve a political union if we have a crisis,” Mr. Schäuble said.

1) the collapse of several reform-minded governments in the European south, 2) a collapse in support for the euro or the EU, 3) an outright electoral victory for radical anti-European parties somewhere in the region, or 4) the effective ungovernability of some Member States once social costs (particularly unemployment) pass a particular level.

oss 100 kroner!

oss 100 kroner!